A Secret Weapon for Teaching Anything? The Nuts and Bolts of Concept Analysis

Do you know how to teach a concept?

As BCBAs, we're always in teaching mode. But let's be real, sometimes we're not quite sure how to get a concept across to our learners. And other times, they might just get it like that without much effort from us. But when a learner isn't getting it, we can’t just change the prompting strategy or put the program on hold (a pet peeve of mine). We have to be ready to mix things up and try new approaches. Especially when it comes to crucial concepts like safety skills. For example, being able to tell the difference between a sidewalk and a street isn’t just another program that we can pass a kid off on for mastering. The kiddo has to get it…they have to conceptualize the difference right to its core. It is that important. This is where concept analysis comes in, and it's a game-changer. It helps us break down concepts into their essential parts and figure out the best ways to teach them.

Behold, a quick rundown on concept analysis.

What makes the thing…the thing.

Let’s pick a concept. Let’s pick a concept near and dear to my heart: what a basketball is. The first step in teaching our learner this concept is through identifying the critical features of the concept. It is to identify what makes a basketball a basketball. So for helping a learner understand the concept of what a basketball is, we have to figure out the features that do so. These features are sometimes called “must have” features. They’re the essentials. This is what every basketball has. Without these things you don’t have a basketball.

Here are critical features for a basketball:

More or less spherical

More or less round

A recognizable pattern of lines that are unique to basketballs

Chances are, when you think of a basketball, you think of a round, spherical, orange thing with black lines in a unique pattern. This is what we call a typical example. For reaching the concept of “basketball”, get your hands on a few pictures of these typical examples.

What other things that the thing might have, but doesn’t need to have?

Next, you have to identify the variable features. These variable features are features that SOME basketballs have but NOT ALL of them. These are also called “can have” features. Basketballs can vary in size, material, and color…but they still hold the critical features that we listed above. Here are variable features of a basketball:

inflation level (can be flat, can be inflated)

what it’s made of (can be rubber, leather, or composite)

size (can be adult sized, junior sized, Little Tykes)

color (can be any color, can be multicolored)

a logo (Adidas, your favorite team, Space Jam, etc.)

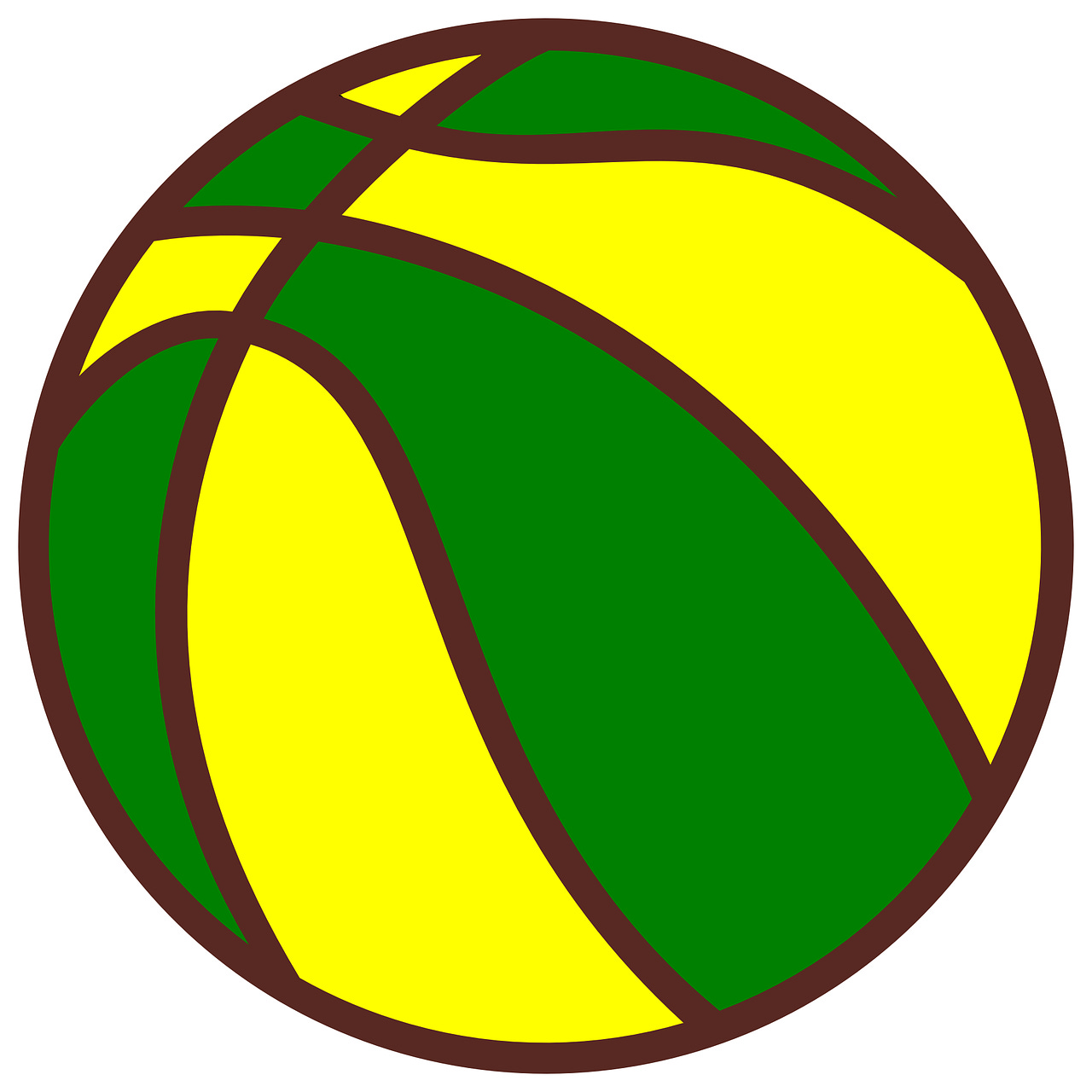

You’ll want to get your hands on as many pictures of basketballs with variable features as you can. We call these far-out examples. Technically, they are basketballs as they possess the critical features to be basketballs…but they might not fit our traditional conception. When I was a kid, Pizza Hut gave out black, Space Jam basketballs with Bugs Bunny’s face on it. This is a far out example of a basketball. Technically it was a basketball…but you aren’t likely to see LeBron use a Space Jam ball in an NBA game. Get as many pictures of these typical examples AND far-out examples as you can.

Now it’s time to come up with some close-in nonexamples These are items that aren’t basketballs…but look pretty darn close. How do you come up with quality close-in nonexamples? Well, you start by looking at the critical features of the concept we’re teaching—in this case basketball. A good close-in nonexample will have most but not all of those critical features.

Remember, we agreed that a basketball was round, spherical, with a recognizable pattern of lines that are unique to basketballs. Here are some examples of ideal close-in nonexamples when teaching basketball:

volleyball: round, spherical, has lines…but lines that aren’t in that unique “basketball pattern” we talked about

baseball/softball: round, spherical, has lines…but lines with stitching

soccer ball: round, spherical, has some lines…but lines and shapes in a different pattern

Get some pictures of as many of these close in, non-examples as you can.

Finally, now that you have a series of typical examples, far-out examples, and close-in, non-examples, you can begin teaching the concept to the learner.

1) Present a small array that consists of atypical example (like an orange basketball with black lines in figure 1, scroll down for image examples).

2) Additionally, add one or two of your close-in, nonexamples (like the volleyball and baseball in figures 3 and 4) to the array.

3) Then give the learner pictures of typical (figure 1) and far-out examples (like the multi-colored basketball) and instruct them to match (say, “Match Basketball!”). Your learner should match the basketballs in the array.

4)Continue to add more and more far out examples while also adding to the array size and adding more close-in, non-examples, as well.

Figure 1, typical example (round, spherical, orange, specific line pattern) :

Figure 2, far-out example (maintains all critical features of a basketball to be a basketball, but doesn’t fit traditional example):

Figure 3 & 4, close-in nonexamples (shares some critical features of a basketball, but not all…which make it not a basketball).

It is also important to note that—given that your learner has demonstrated the ability to receptively identify pictures in large arrays—you can have them “find the basketball” in addition to matching. If they possess the intraverbal/tacting capabilities, you can have them tack the critical features of a basketball as well.

Also, note that this is a woeful over-simplification of the concept analysis process. I recommend—in fact, I insist—that you check out this article on the process.

Tangential, ABA nerd out with a real life application regarding concept analysis:

A great many disagreements in our daily life are said to occur thanks to two people being on opposite sides of a certain issue. I think this isn’t that simple. Disagreements are not due to two opposites not seeing eye to eye. Instead, they are largely due to two sames not seeing eye to eye on a critical feature of an issue, concept, or definition. Further, we often fail to identify what these critical features are. As such, we speak in broad generalizations when responding to the argument. “You never want to eat where I want to eat.” “You only think LeBron is the greatest because you’re a Lakers fan!” See examples below. (Also he’s not.)

For the sake of relationships and finding truth, this can be harmful.

For example, two spouses who generally argue about where to go to dinner on a date night aren’t disagreeing about restaurants. Instead, they’re usually incongruent on what the definition or concept is of a date night dinner. They’re unaware of their own standards—the critical features they have implicitly set for the evening in regard to what constitutes a quality night out. Understanding what you both consider to be the critical features of a night out is a valuable step in going on a dinner date. Is there a specific atmosphere you’re looking for? Does the food have to be authentic? Does it have to be local?

Likewise, two friends disagreeing on who is a better professional athlete aren’t disagreeing on the athletes themselves. Instead, they’re actually not seeing eye to eye on what they both uniquely consider to be the critical features that embodies what a quality athlete should be. Better to start the debate by establishing the critical features of what a pro athlete is. Is it more championships? More points? More yards? More wins?

Next time you find yourself in disagreement with someone on something, consider exploring the critical features to the concept. It might not be the argument that is of issue but—instead—the critical features regarding the concept (or topic) itself.

Happy Friday!

Have a clinical question and want to nerd out about it? Join our exclusive Facebook Group!

Johnson, K., & Bulla, A. J. (2021). Creating the Components for Teaching Concepts. Behavior analysis in practice, 14(3), 785–792. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-021-00626-z